The best protection any woman can have... is courage.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Portraits of seven prominent suffragists: Mott, Greenwood, Stanton, Dickinson, Livermore, Anthony, and Child. Library of Congress.

Reformers on the Lecture Circuit

RELATED PEOPLE

RELATED RESOURCES

Before women’s rights activists established national organizations in 1869, the women’s rights movement was oriented around grassroots, local activism. Women met at annual conventions, read women’s rights newspapers, and attended lectures. Going to a lecture might not sound fun to us, but they were a very popular form of entertainment in the nineteenth century. Speakers discussed a range of topics, such as politics, spiritualism, vegetarianism, and phrenology (the study of the contours of your head to determine your strengths and weaknesses).

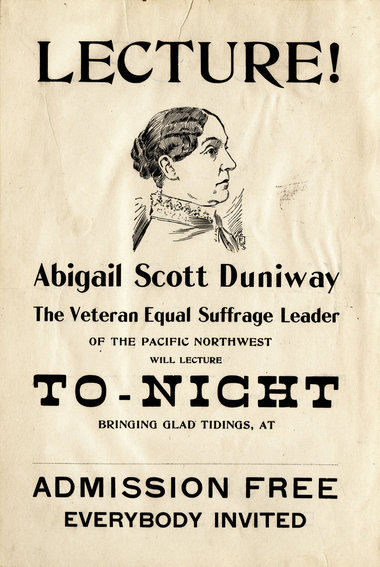

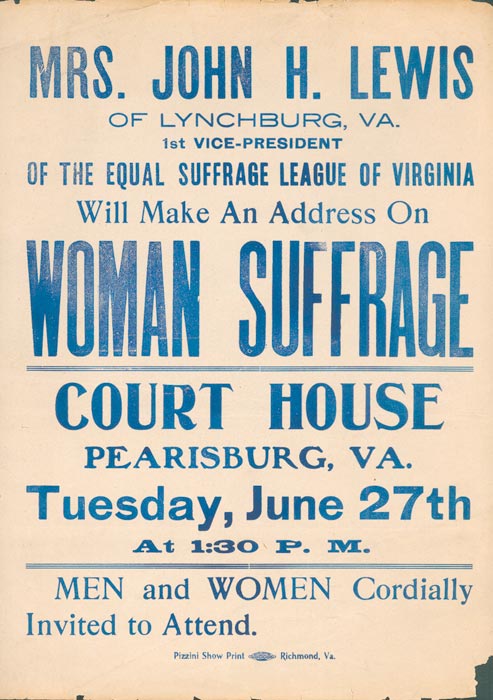

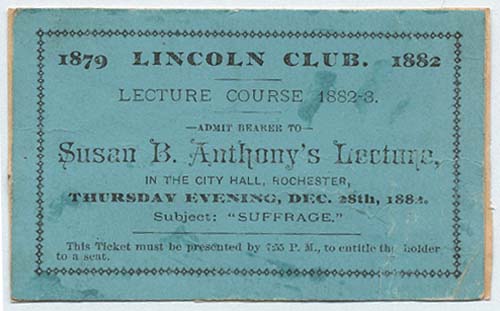

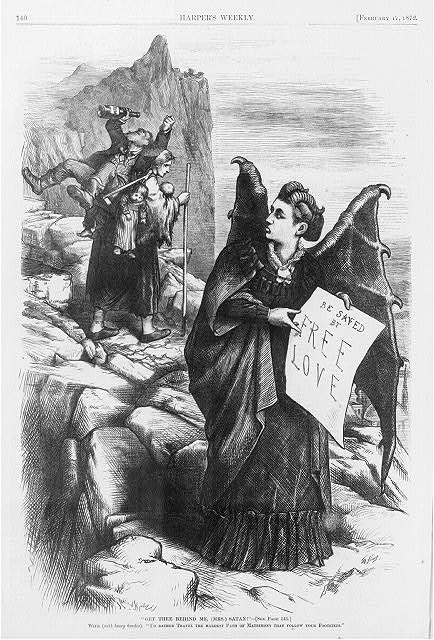

In the 1860s and 1870s, women’s rights activists took to the lecture circuit to win supporters for their cause. Anna Dickinson was one of the most popular speakers of the era. She even spoke before Congress. Sojourner Truth attracted attention as one of the few black women who lectured widely in support of the rights of women and African Americans. In 1872, Victoria Woodhull—a popular lecturer, stockbroker, and self-proclaimed psychic—became the first woman to run for president. Elizabeth Cady Stanton traveled the nation to support women’s rights, an activity she preferred to organizational duties. Some women’s rights lecturers spoke as many as 200 nights a year. The money they earned from their lectures helped support them and their cause.

By Allison Lange, Ph.D.

Fall 2015

Essential Questions

- Why did so many women fight for suffrage as individuals during this period rather than as part of an organization?

- What made the lecture circuit become popular?

Public domain.

Julia Ward Howe co-founded the American Woman Suffrage Association and helped start its paper, the Woman’s Journal. In the essay “Modern Society,” published in 1881, Howe wrote about the French system of representation and the problems of worshipping wealth. She also explained why women’s education had been so poor and the need to improve it. Howe felt that women’s minds had been imprisoned by society and needed to be freed so they could be properly used.